Trailers: For the Long Haul

By Diane M. Calabrese / Published March 2017

A wagon is the first trailer most people learn about. Soon after walking, kids learn how to move groups of favorite belongings with a wagon. It doesn’t take long to realize a wagon can exhibit independence, but this creates a bit of peril. Unsecured loads can fall, and the wagon can become unstable and tip over on rough ground. In fact, if one’s grip was not a tight one, the wagon and its load could get away from him or her.

It could be written that everything one needs to know about the structure and function of trailers one learned before going to kindergarten, given contemporary features of trailers have analogs in simple wagons. The regulations surrounding trailers, though, take one into a very adult world.

In August 2016, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Department of Transportation’s National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (DOT–NHTSA) finalized greenhouse gas (GHG) and fuel-efficiency standards for heavy-duty trucks. EPA and NHTSA are now in the process of finalizing fuel-efficiency and GHG standards for trailers.

Some trailers used in the pressure washing industry will be affected by the EPA’s GHG standards beginning in 2018. The NHTSA standards will take effect in 2021, but even before that year, there will be credits available for voluntary participation.

The EPA and NHTSA standards for trailers promote among other things structural arrangements (such as light-weight construction), self-inflating tires, and aerodynamic embellishments. Design changes in trailers are just the most recent of the many interests regulators have in trailers.

The new standards add to the responsibilities of manufacturers. The compliance provisions are stringent. Among them are strict test procedures, enforcement audits, and protection against devices that could be used to undermine the features built into the trailers meeting new standards.

Yes, we are a long way from childhood and a longer way still from the earliest methods of dragging a load. Timber harvesters tied and skidded logs using the power of horses or mules. In Asia, elephants that long supplied the power for skidding logs have only recently been supplanted by mechanical methods.

Skidding followed a progression that began with dragging raw materials across the ground—as the stones for the Washington Monument were skidded to the place where the familiar obelisk now stands. Flat platforms, which were called skids, were subsequently used to support materials and the skid was dragged. When the flat platform was affixed with wheels, it became a trailer (cart, wagon, and all early names apply).

In our industry, trailers are not only used to convey equipment to jobsites, they are also used (in lighter-weight and smaller versions) to support pressure washers so that the pressure washers can be moved around at a jobsite. There are also trailer configurations that fit both categories—on-road and off-road capabilities.

Manufacturers aim to make it as simple as possible for contractors to choose the trailer or trailers that best match their requirements. For instance, makers of light- and medium-duty trailers can join the National Association of Trailer Manufacturers (NATM), which is headquartered in Topeka, KS. Compliance consultants from NATM visit member facilities and review the manufacturing processes in place, all as part of ensuring that federal standards are being met.

The responsibilities of trailer manufacturers are many—and as we see, they are growing. End users of trailers, such as contractors in our industry, have at least as many responsibilities.

Manufacturer’s Perspective

Everything begins, continues, and culminates with compliance. That’s the perspective of the manufacturer. Kärcher North America Inc., which is headquartered in Camas, WA, illustrates the seriousness of the approach. “As a manufacturer, we do sell trailers with pressure washer equipment, tanks, hose reels, and storage fully tested and compliant to the NHTSA safety standards certified by the NATM,” says Bill Ott, the executive vice president of product development and quality at the company.

“These certifications should be compliant to a fully loaded—water, fuel, etc.—GVWR [gross vehicle weight rating] and should include braking systems as required by these standards,” explains Ott. “From a design perspective, the trailer should include the appropriate quantity of wheels and wheel-base dimensions recommended by these standards. In addition, the fully-loaded trailer must have a center of gravity aligned over the wheels to maximize safety.”

It’s a matter of producing the optimal configuration for the end user of the trailer within the context of following all applicable standards. “Certainly, the layout of the equipment should be such to optimize operator productivity and ease of setup and storage,” says Ott. “But first and foremost, the trailer needs to be certified to drive on highways to ensure safety of the driver and other vehicle traffic.”

There is no way to overstate the responsibilities that manufacturer, distributor, and contractor have in ensuring that trailers are built according to federal standards and used in compliance with federal standards. Ott emphasizes the point.

“I cannot stress enough the importance of safety and ensuring the cleaning equipment setups align to NHTSA and NATM [standards],” says Ott. “There are more trailers purchased and configured directly by dealers, so as a manufacturer we do lose some control over safety when this occurs.”

Distributors must be as aware of regulations governing trailers as are manufacturers. “Most dealers do understand the safety requirements, but do not pursue the NATM certification,” says Ott. [Such certification may be something that more dealers will want to consider in the future, especially as new standards begin to take effect in 2018.]

At some juncture, the contractor must be committed to obtain training in proper use of any trailer in service. The training could be obtained from a distributor, via a course offered through a professional organization, or through a private entity that offers instruction.

“Regardless of where training is obtained, the end user must also be trained on proper safety procedures and driving guidelines to reduce risk,” says Ott. “Many trailers are not rated for typical highway speeds, and the operators need to comply with these guidelines to keep the industry safe and minimize litigation.”

Contractors

Using a trailer is not as simple as buying a trailer, loading it, and hitting the road. Using a trailer requires meeting all regulations that apply. If there’s ever a point of hesitation in doing so, it could lead to a great deal of trouble and liability, so don’t even think of it.

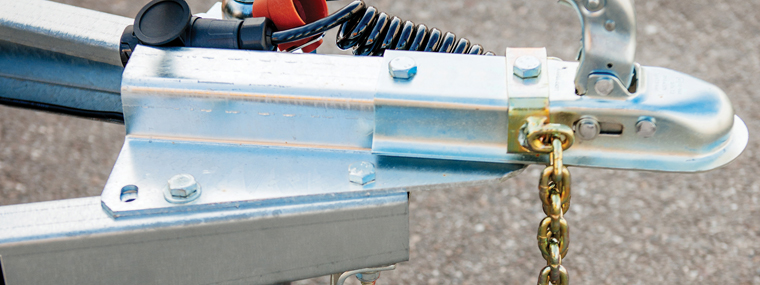

Contractors have obligations to meet in terms of how loads are tied down (how many ties, rub guards or edge protection, etc.), adherence to weight limits, and signaling requirements. An on-road trailer must meet an additional array of state and federal requirements for brakes on axles, lighting, load balance, and point of attachment.

There is also the issue of a USDOT number. The Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration offers an online tool that enables commercial vehicle owners to determine whether or not they need a number. (See www.fmcsa.dot.gov/registration/do-i-need-usdot-number).

The DOT does not require a number when not transporting hazardous material or when gross vehicle weight is under 10,001 pounds. But approximately two-thirds of states require a number irrespective of load or weight, so most contractors must get one. (The unique DOT number is used to collect safety information and conduct audits and inspections, as well as to investigate incidents.)

Many contractors do not use trailers, and making a decision about which way to go depends on many factors, such as geographic area, size of team, equipment in use, and whether large ancillary equipment is ever needed (e.g., lifts for working high). One option is to subcontract for hauling of large ancillary equipment, sidestepping issues associated with trailer ownership.

“The major advantage of a trailer over a box truck is the access to the equipment, water, and fuel tanks to increase the productivity on the job,” says Ott. “The equipment can be easily arranged to maximize equipment access, and in many cases results in a smaller footprint.”

The best reasons for choosing trailer or box truck or both emerge from a clear assessment of the end user’s needs. “Certainly, box trucks have their place and are recommended in colder climates and to keep the equipment out of the elements,” says Ott. “Our pressure washers are specified to be stored in a closed facility when not in use so you get that easily with a box truck.”

In a world committed to economy of scale that reduces fuel use, a trailer has another advantage over a box truck. “You can disconnect a trailer and park it at a jobsite,” says Don Kotula, founder and chief executive officer of Northern Tool + Equipment in Burnsville, MN.

Knowing “how much weight you’re going to haul” on a regular basis is a good place to begin when buying a trailer, says Kotula. The more precise the match, the more efficiency gained.

Finally, once the trailer is part of the equipment roster, tend to it carefully (like all equipment). “You want insurance,” says Kotula, “and you want to keep your trailer in good shape—good tires, lights working, etc.”