Safety Basics at Heights

By Diane M. Calabrese / Published April 2020

Flying without a net. Circus trapeze artists knew the risk. Today, circuses are fading into history. Aerial performers—apart from the outside-the-tent daredevils leaping buildings—work with nets.

So, what explains any failure to follow safety basics on jobsites? Even in the most regulated states, we observe serious lapses in residential and commercial areas. In Maryland, start the what-we’ve-seen list with unstable scaffolds, absent harnesses, and metal ladders tangling with electric wires.

The psychology of employees who depart from safety basics when working high is akin to the risk netless fliers took. Unfortunately, their inherent desire to test risk endangers them, their coworkers, and passersby.

Falling—from heights and from ground level—is one of the leading causes of injury and death in the workplace. Obstacles and slippery surfaces cause many falls at ground level. They do the same at heights.

The risk of falling is compounded by altered mental states caused by lack of sleep, illness, and the use of pharmaceutical or recreational drugs. Reducing the risk of falling begins with an awareness of one’s surroundings. It is bolstered by adherence to all safety protocols.

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) provides extensive guidance on correct use of ladders, harnesses, and scaffolds. Essential points are covered below.

Before moving to them, however, let’s get some insight into how to implement and sustain a strong safety program when working at heights. Keep in mind the definition of a high structure varies greatly and spans settings from New York City to Dodge City, KS.

Excellent Training

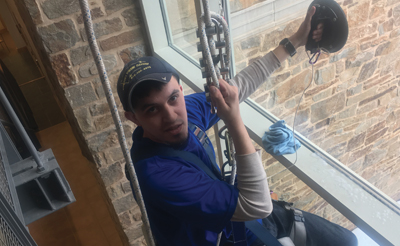

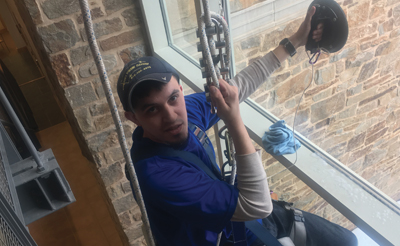

“Here in upstate New York, my company does not come across a lot of high-rise work,” says Ken Bullinger, owner of Ken’s Window Cleaning Inc. in East Schodack, NY. “We do come across jobs that require we know how to safely rappel. We even have jobs that have anchoring trolleys that require we rappel inside of buildings.”

A good way to ensure employees understand safety basics is to tap the expertise of a professional safety instructor. That’s what Bullinger did.

“The best avenue of safety I have ever pursued is hiring Stefan Bright to come to our shop and give the team a safety seminar on rope descent and rescue and safety,” says Bullinger. “The information, professionalism, confidence, and resources are the building blocks for any safety issues we have. He was able to certify our team and educate in a manner that demonstrated the seriousness of the procedures while providing the confidence that it can be done safely.”

Stefan Bright is a partner and the general manager at Valcourt Safety Systems LLC, which is headquartered in McClean, VA. He has given many industry-level seminars to groups we know well, such as the IWCA (Inter-national Window Cleaning Association).

One countercurrent that owners of businesses that work high must constantly work against is the employee who—like the trapeze artist we cannot fully understand—has a risk-taking spirit. Vigilance on the part of the owner is a must.

“The biggest impediment to safety is what I call the ‘cowboy attitude,’” says Bullinger. “A team member may feel years of experience, skill level, natural abilities, a need to show off, or being in a rush allow him to bypass safety procedures and/or suggestions. This attitude spreads very fast. A good manager will always make sure the crew knows that safety is far more important than speed or ego.”

“The biggest impediment to safety is what I call the ‘cowboy attitude,’” says Bullinger. “A team member may feel years of experience, skill level, natural abilities, a need to show off, or being in a rush allow him to bypass safety procedures and/or suggestions. This attitude spreads very fast. A good manager will always make sure the crew knows that safety is far more important than speed or ego.”

So, yes, training (and retraining, refreshing) coupled with a methodical approach keeps workers at heights safe. Workers are even safer if they never leave the ground, and finding ways to keep them on the ground as they conduct the job is something that should be considered as the most logical option, when feasible.

“The first step in any situation that requires descent is to try and find any other way to get the job done,” explains Bullinger. “We have spent a lot of resources and time expanding our water-fed pole abilities and accepting the cost of aerial lifts to avoid descent.”

From The Top

On December 17, 2019, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) at the U.S. Department of Labor released its tally of fatal occupational injuries in 2018. Fatal falls or slips and trips accounted for 791 deaths, or 15 percent of the 5,250 on-the-job fatalities. Transportation-related incidents accounted for 40 percent.

OSHA offers abundant guidance in its regulations concerning fall protection, but difficulties begin with the separate set of standards for the construction industry. Standards that apply to our industry are largely part of general industry standards. Obviously, there’s considerable overlap.

Difficulties continue because standards may be interpreted differently, depending on site-specific parameters, etc. Official letters of interpretation are among the resources contractors, distributors, and manufacturers can tap to fully understand their obligations.

General industry standards for fall protection are part of 29 CFR 1910. They include specific entries for elevating tools and elevated components, such as ladders (1910.23), scaffolds, and rope descent systems (1910.27), and personal fall protection systems (1910.140).

Many professional organizations provide their own guidance about fall protection. In doing so, they clarify and sometimes augment OSHA standards. For example, the American National Standards Institute (ANSI) and the International Window Clean-ing Association (IWCA) have a joint standard that applies in one part to the use of window cleaning equipment and in the other part to manufacturers and installers of the equipment.

Many professional organizations provide their own guidance about fall protection. In doing so, they clarify and sometimes augment OSHA standards. For example, the American National Standards Institute (ANSI) and the International Window Clean-ing Association (IWCA) have a joint standard that applies in one part to the use of window cleaning equipment and in the other part to manufacturers and installers of the equipment.

In 2017, OSHA updated general industry standards for fall protection and added requirements for personal fall protection. (See www.osha.gov/walking-working-surfaces/index.html.) This is a good starting point for understanding the range of regulations that affect a business in which workers are on elevated surfaces or structures.

For example, in addition to ensuring workers must be trained in the use of equipment, the equipment used for rope descent systems must be inspected and certified. Workers using ladders higher than 24 feet must have a ladder safety system or a cage or well. They also must have a personal fall arrest system. (At the end of 2018, safety cages were excluded as a substitute for fall protection.)

OSHA guidelines may be made more stringent by state regulators. Depending upon the state in which a company is working, there may be additional requirements for fall protection.

To drive home the danger of working without fall protection, OSHA offers some accounts of what can happen. Given its OSHA Fatal Facts No. 10 (2015), Engulfment in a Sugar Hopper, all should understand that sometimes a fall just begins the trouble for a worker.

Guard rails and toe boards are among the protocols for manufacturers that require workers to be on elevated platforms or walkways. There may be vats of chemicals or conveyors—not just a hard surface—below. If there is just a floor below, four feet is the threshold height for requiring rails and boards. If there is machinery below, the standard applies at any height.

OSHA offers a variety of eTool and QuickCard™ primers that condense the extensive standards that apply to lifts, scaffolds, and ladders. The scaffolding eTool covers not just scaffolds but also any vehicle-mounted lift used to elevate workers (i.e., extendable boom platforms, aerial ladders, articulating boom platforms, vertical towers, and combinations of the foregoing).

Lifts add some risks even as they minimize others. They can tip over or move in a way that ejects a worker. Electric shock through entanglement is another of the hazards. Workers who will use lifts must be trained in how to do required inspections (pre-start and routine maintenance) and the manufacturer’s instructions for use.

Scaffolds may take many forms. The OSHA requirements for scaffolds cover weight-bearing ability, bracket placement, and width and height. In addition to general requirements, OSHA gives specific guidelines for scaffolds. The scaffolding eTool reviews requirements for specialty scaffolds. OSHA offers a frame or fabricated supported scaffolding module that applies to all types of supported scaffolds.

Ladders are probably the most-used elevating aid in our industry. An OSHA QuickCard covers portable ladder safety, which is detailed in CFR 1926.1053. The QuickCard includes fundamental reminders, such as not to exceed the load rating for the ladder (remembering to add weight of equipment to load) and to avoid electrical hazards. The standard prescribes everything from the interval placement of rest platforms and self-retracting lifelines to cage and well design and size.

Whether on a ladder or a scaffold or in a lift, some safety basics for elevated work are universal. A clear mind, slip-resistant footwear, and attention to ambient conditions (e.g., no excessive wind speed) top the list.

Net or no net, trapeze artists always checked their rigging before relying on it. Check all equipment—even a faithful ladder—before putting it in service. Always use the metaphorical equipment of a net—the required harness, toe guards, rails, etc. And for maximum safety, keep feet on the ground whenever possible.