Masonry and Brick Cleaning—New Construction, Part II

By Terri Perrin, with technical support from the Brick Industry Association and Ron Baer, Unique Industries / Published February 2022

Editor’s Note: This is the second part of an article focus-ing on brick and masonry cleaning. To read the first part for a more complete picture of what is required, visit www.cleanertimes.com or pick up your January 2022 issue and read the first part on page 62.

Tips and Techniques

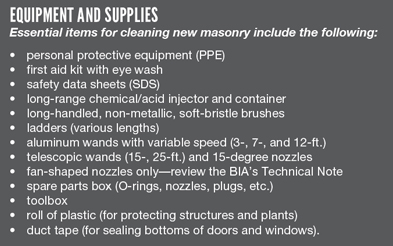

There are a number of ways to clean masonry. For this article, we will concentrate on pressure washing. Be aware that pressure washing is not appropriate for some brick or masonry materials.

For all methods listed below, it is imperative to pre-wet the surface to be cleaned and to keep the entire area wet during the cleaning process. Always remember that many bricks have beautiful colored surfaces or coatings and colored sand finishes that add to their character, and cleaning new masonry is distinctly different from cleaning and/or restoration of existing masonry. Your goal with cleaning is to remove only the excess mortar or dirt, not the imperfections and beauty inherent in the natural brick.

For all methods listed below, it is imperative to pre-wet the surface to be cleaned and to keep the entire area wet during the cleaning process. Always remember that many bricks have beautiful colored surfaces or coatings and colored sand finishes that add to their character, and cleaning new masonry is distinctly different from cleaning and/or restoration of existing masonry. Your goal with cleaning is to remove only the excess mortar or dirt, not the imperfections and beauty inherent in the natural brick.

Brick and masonry cleaning methods include bucket and brush cleaning, pressure washing, poultice, micro-abrasives, lasers, and special methods to remove stains.

Pre-wetting and rinsing dos and don’ts:

- Determine whether any areas will require special attention and/or protection. Stand about 40 feet back from the structure and look for areas of concern, such as louvers or soffits.

- If there are big clumps of mortar smear, pre-wash scraping can be done in a systematic manner (so that no spots are overlooked). Work in small sections to get consistent results. Scraping prior to cleaning reduces the surface area of mortar on the structure, which in turn reduces dwell time for the chemical on the surface.

- Pre-scrape brushes should be long-handled with non-metallic stiff bristles. Never use metal fiber brushes or tools as they may damage mortar joints or leave metal fragments behind that could oxidize (rust) and result in further staining.

- Proper pre-wetting ensures that applied cleaning products stay on the surface. If chemicals are absorbed, they may not be able to be removed and can cause discoloration to the brick.

- Flood the surface with water using a stainless steel 15-to-45- degree fan tip, held 12-to-18 inches from the brick surface, ideally at about 100 to 400 psi on the wall/contact/impact point. (The lower the better.) Note that if you are holding the wand at the recommended distance, the point of impact (pressure) on the wall surface will be less than the setting on the pressure washer.

- Never use water pressure higher than 400 psi unless permitted by the brick manufacturer. Saturate the area to be cleaned and the surrounding surfaces and keep them wet until the final rinse. Rinsing removes loosened components of mortar, sand, and chemicals.

- If using a lift or scaffolding, work on tall walls may require a second team member to rinse the wall below the area being cleaned. This will help to prevent any chemical drips from contacting a dry area.

Cleaning dos and don’ts:

- Pressure washing begins after scraping (if required).

- Follow the manufacturer’s instructions on how to mix cleaning products. To avoid splashing, always add chemicals to water, never vice versa.

- Review the manufacturer’s safety data sheets (SDS) and recommended handling practices.

- Follow all OSHA requirements relating to the safe handling and use of chemicals.

- Apply cleaning solution to the wet wall (according to the cleaner manufacturer’s instructions) by brush or low-pressure pump sprayer with a wide-angle fan-shaped sprayer nozzle tip, maximum 30 to 50 psi. Never use higher pressure as doing so can drive the cleaning solution deep into the pores of the masonry where it will be difficult to remove.

- Start at the top corner of the wall and move down. (Or move bottom up, if that’s what the cleaner manufacturer recommends.) Work in areas small enough so that excess mortar can be removed before the water dries.

- The combination of heat, pressure, amount and effectiveness of chemicals, and agitation (rate of PSI and type of spray nozzle) determines the speed and efficacy of cleaning. Using warm or hot water can be more effective than cold water. Scrubbing with a brush also achieves heat and agitation but can be tedious and not as effective.

- Clean the wall in smaller sections, starting at the top and working down. Make sure to overlap each run with the wand. Evaluate and make pressure (always the lowest possible) and nozzle adjustments across the first few feet of the target area as required.

- Move downward and overlap cleaning solution and water on successive spans, like mowing your lawn. Use visual reference points to ensure vertical and horizontal overlap.

- Rinse each section with clean water from top to bottom using a stainless steel 15-to-45-degree fan tip held 12-to-18 inches from the brick surface, ideally at less than 400 psi.

- During rinsing, monitor the appearance of the runoff. Clear runoff at the base of the wall indicates adequate rinsing. In addition, the pH of the wall surface and the water runoff should be checked periodically with pH paper to confirm that both are returned to neutral (pH 6.5 to 7.5). Additional rinsing is needed if the pH is outside these values in either direction (too acidic or too basic). Measure the pH of the wall surface again 48 hours after cleaning has been completed, when the wall is dry. If the pH is not neutral, then rinse the surface until neutral pH is achieved.

- Use clear water to rinse any over-spray, brick dust, or mortar from soffits, fascia boards, windows, woodwork, etc.

- Remember, the best tools are experience and the correct cleaning products. Do not over-clean the brick.

Exceptions

Sand-surface bricks: Get specialized instruction before tackling sand-face brick. To avoid removing the sand finish, cleaning with pressurized water is not recommended. Brush cleaning with light pressure is needed. Strictly follow manufacturer requirements for cleaning products to be used on these bricks.

Concrete masonry units (CMUs): In some cases, especially with CMUs, a rotating nozzle may be a good choice for new masonry cleaning. But test the nozzle first on a concealed area, evaluating the test

results after complete drying. Concrete masonry may require additional labor to clean. Excess mortar sometimes must be chiseled off.

Ancillaries

Focus matters when cleaning new masonry. Ancillaries may include brick patios or decorative walls that are part of new construction.

New masonry cleaning takes different skills and equipment than general cleaning. It is a significant and required part of the construction process. Cleaning of existing masonry buildings is similar to cleaning new masonry construction but requires a different approach and more experience and training.

Water used for cleaning should be potable (suitable for drinking). Iron content should be less than two parts per million by weight. Determine whether the local water includes additives, water softeners, or other agents that may cause issues if used for cleaning.

Weather matters! Be aware that air temperature, temperature of the masonry, and wind conditions may all affect drying time and the reaction rate of cleaning solutions. Avoid cleaning when weather is anticipated to be below 40°F during cleaning and for the following week.

Brick texture may influence the efficacy of cleaning operations. Smooth-textured brick is easier to clean.

Ventilation louvers are often located at the top of brick homes (or other structures). Take special care not to spray water inside as it may go directly into the attic.

Acidic materials will turn hardwood floors black. Be certain that windows and doors have been sealed properly to prevent the interior floors from getting wet.

Do not get water in foundation vents, which are in place to keep the crawl space dry. A wet crawl space could result in a citation from a building inspector—and a loss of future opportunities to the contract cleaner.

Acidic chemicals tarnish copper, so cover copper unless the building owner wants an aged look.

Once you know what you are doing, masonry cleaning for new construction is, for the most part, relatively simple. But beware that there are significant liability issues if anything goes awry. Masonry—particularly brick and natural stone—is as sensitive (e.g., to discoloration or damage) as it is beautiful. Always get proper appropriate training before entering this niche.

How To Bill

Submit your bid or estimate with full details of the specific job conditions. For example: Will there be other contractors still on site or working on adjacent units?

When will it be possible to work on the project? (i.e., during which hours and on which days?)

Will the client supply a lift or scaffolding, if required, and who will provide the required safety training? Who will set and reset scaffolding?

Will the client supply or specify the cleaning chemical?

Verify access to a potable water supply.

Get a detailed list of all structures and elements that should be protected and those to be cleaned.

Provide proof of liability insurance and/or bonding. (This will be required by most builders and property managers.)

Know whether there are labor union rules and standards that will apply.

Clearly delineate payment method and timing in the contract.

Be aware of wastewater run-off/environmental regulations.

Other Billing Considerations

Be alert to a clause in the contract giving the masonry contractor or the general contractor, whichever is the customer of the cleaning contractor, the right to delay or withhold payment if their own payment is delayed or withheld. Such delays on construction projects can be weeks, months, or even years long—much more than a cleaning contractor wants to absorb.

Bids to builders and project managers are generally in the form of a flat cost per square foot. Weigh all factors and take accurate measurements before making a bid. If there is an opportunity to inspect another project being completed by a prospective client, seize it. Get an indication how neat (or untidy) the masons generally are. This information will help you determine how much time and chemicals will be needed to complete the job.

Manual cleaning product application and scraping proceed at approximately 800-square-feet of cleaning per man, per eight-hour day. In addition, there is typically the need for an extra person to turn the washer on and off when the cleaning product is being applied, to refill cleaning products, and to help keep the wall wet.

Using a specialized machine, such as the Kem-O-Kleen masonry cleaning machine, the average movement on a typical brick job is about 2,600 square feet per day, per man, with the occasional need for a second person on the ground. These production rates may differ when using other types of pressurized equipment.

Estimate according to the cleaning product recommendations. Keep track of actual usage to improve the accuracy of subsequent estimates.

Ron Baer is vice president of Unique Industries-Kem-O-Kleen in Denver, CO, and is a member of Masonry Contractors Association of America. He has been involved in the masonry cleaning industry for over 30 years. Ron is a frequent contributor to masonry cleaning articles in Masonry magazine and other trade periodicals.

The Brick Industry Association (BIA) provides a broad range of programs and services that fulfill its mission of promoting and safeguarding the clay brick industry. BIA promotes the industry through education and promotional programs, safeguards the industry through comprehensive advocacy and compliance efforts at the federal and state levels, provides representation in all model building code forums and national standards committees, and is involved in local advocacy programs that educate local planning and elected officials about clay brick. www.gobrick.com.