How to Deal with Metered Water

By Diane M. Calabrese / Published May 2018

Here’s a challenge for readers who are particularly good at making a guesstimate: How many public water systems are there in the United States?

According to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), there are more than 151,000 public water systems. To be fair, the EPA includes in the category any system that delivers water for human consumption through constructed conveyances, which are usually pipes, to a minimum of 15 connections or 25 people for no fewer than 60 days each year.

EPA classifies water systems as community (supplies water to same population year-round), non-transient-non-community (schools, factories, hospitals, office buildings with their own water systems), and transient non-community (campground).

The many different publicly- and privately-owned water systems serve 90 percent of Americans. Metering water use and charging customers according to use is one way the systems fund maintenance.

“Basically, all water is metered in some way or form,” says Ray Burke, owner of Spray Wash Exterior Cleaning LLC in Tallahassee, FL. “Even a well powered by electricity has a meter on it—in the form of an electric box; so in one way, shape, or form, everybody is paying for water.”

Aquifers supply the water in the north Florida region where Burke’s company does business. “And thankfully, we have plenty of water,” he says. “In fact, I don’t even remember the last time we had any watering-type restrictions.”

For many jobs, Burke’s team can use the customer’s water for the project being done. “Sometimes we need to rent a hydrant meter from the city [or] county,” he explains. “In that case, the meter is read by the city, and we are billed for water used.”

Metering is a complex issue. Strategies taken by owners of water systems to take in sufficient revenue to keep infrastructure intact and updated vary widely. Take the meter at the hydrant versus the meter at a residence or commercial building as one example (in one place).

The Washington Suburban Sanitary Commission (WSSC), which provides water to the District of Columbia and most parts of adjacent Montgomery County and Prince George’s County in Maryland, allows fire hydrant metered use with an approved lease application. Intended use, business identification, chemicals being used, and valid proof of residency via a driver’s license are required to make an application.

With a permit in hand, a contractor can tap hydrant water from WSSC for as many as six months. There is a hefty deposit required for the meter. The water charge is $7.77 per 1,000 gallons (March 2018), which puts the consumption charge in line with water being delivered through pipes.

There is a boon to contractors getting a large amount of water from the WSSC from a hydrant because they do not have to pay sewer charges. Sewer rate charges for piped water

are approximately 25 percent higher than water consumption charges, and they are computed based on water consumption.

WSSC rates for pipe-delivered water per 1,000 gallons of consumption increase to a maximum of $8.16 for 9,000 gallons or more. The corresponding top sewer rate is $11.20 per 1,000 gallons for a combined rate of $19.36, which is 120 percent more than the hydrant charge of $7.77.

If a contractor is going to be completing a project for a client that will require a large volume of water, such as cleaning a newly installed in-ground pool and then filling it, the hydrant meter may make sense. For the most part, however, the jobs completed for residential clients can be done without causing an appreciable bump in the client’s water bill.

Getting It Right

Customers almost always understand that if their water is being used, they will see an increase in their water bill, says Barry Shields, owner of Shields Outdoor Services in Ocala, FL. It takes water to clean, and customers understand that.

“Some customers will say things like, ‘I guess my water bill is going up this month,’” says Shields. But it’s more just a matter-of-fact statement, he explains. “Homeowners know it takes water to clean.”

Shields, too, is working in a region where water is relatively plentiful. He suggests that in regions where there are issues of drought or arid conditions year around, metered water might be a greater concern.

If a contractor must truck in water, there is a cost attached to the transport. In some cases, the cost of transporting—to distant spots—might have to be passed on to the customer. Shields emphasizes that almost all his customers realize that a slight uptick in their usage for an interval will occur because a contractor is using their pipe-supplied water. And it has never been an issue to stop a job from proceeding.

The rate structures for water use include flat fee, uniform, increasing block, and declining block, as well as seasonal and drought. Flat fee in which all customers are charged the same fee have become rare because they provide too little revenue to maintain systems. Increasing block rates, such as those used by the WSSC, are common in urban areas, and they are intended to encourage conservation. Declining block rates—use more, pay less per unit—are more common in rural areas or where water is abundant.

Robert M. Hinderliter, an environmental consultant and well-known member of our industry based in Fort Worth, TX, notes there are still places where water is not metered in his region. Using hydrant water is a different matter. “Here, if you hook up to a fire plug, you have to have a construction meter,” says Hinderliter.

The responsibility to obtain a construction meter is one the contractor should consider part of doing business. There are instances of individuals taking water from hydrants without the requisite meter or permission. That would be “getting water you are not paying for,” explains Hinderliter.

“Metered water becomes important during a drought,” says Hinderliter. Under prolonged dry conditions, restrictions may be on water use. The metering allows water systems to check on use and determine whether customers, including those at hydrants, are using more than a ration goal (whether soft or arbitrary).

In addition, many water systems increase water rates with drought level. Some do the same with season.

Hinderliter does not see metered water as a big factor in helping meet the goals of the Clean Water Act. “The contract cleaner is insignificant” in terms of water use, he explains.

An advocate for developing and following best practices and engagement on environmental issues, Hinderliter anticipates that contract cleaners will be using the minimum amount of water, and they will be collecting and handling wastewater in the proper manner.

Meters have a way of nudging consumers to use water more efficiently. The Water Sense program at EPA highlighted the water savings made by H.E.B. car wash facilities in San Antonio, Texas, in 2012. The 24 car wash facilities in the group were able to cut water use by more than 24,000,000 gallons annually by upgrading to high-efficiency reverse osmosis units and reclamation systems.

The measurement of water use by the facilities in San Antonio included a bonus. Metering detected a loss in efficiency in some reverse osmosis units and the units were replaced.

Meter as Ally

Just as walkers and runners measure steps and strides with meters in order to evaluate and modify their approach to exercise, contractors and in-house cleaning systems gain by knowing as much as possible about the amount of water being used. A surprise jump in usage may indicate a problem with a machine or an in-line system.

The trend with water meters is toward more of them. Seeing the water meter as an ally to the industry puts everyone–contractor, in-plant cleaning system, distributor, and manufacturer on a positive plane.

On February 8, 2018, the Denmark-based company Kamstrup opened a U.S. manufacturing facility in Roswell, GA. Kamstrup manufactures intelligent, or smart, water meters that are deployed in almost every conceivable water-monitoring context.

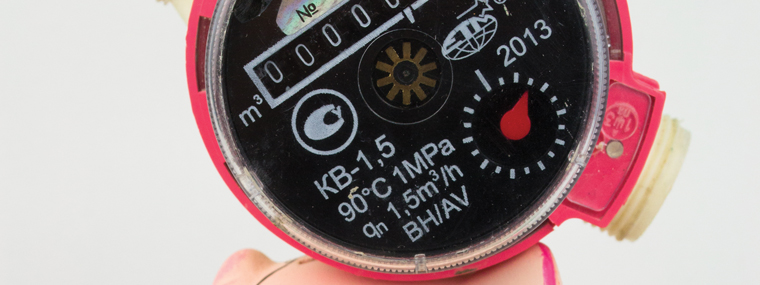

A Kamstrup meter uses ultrasonic principles to measure and log consumption. Data are transmitted electronically to readers. With meters placed throughout a water system, a system operator can quickly be alerted to changes that indicate burst pipes and other problems. The precision of the meters also shores up accuracy. One case study indicated a utility can increase revenue three percent by using static ultrasonic water meters instead of mechanical meters.

With water increasingly recognized as the precious resource it is, we can expect metering of water to increase. Members of our industry have been looking ahead for years with the design of equipment that uses the smallest amount of water to do the most work, and to the incorporation of methods for reclamation and recycling.

Adding meters at strategic points on equipment or across in-line systems will give end users and manufacturers more information about water use, which can be used to improve practices on the user side and innovate on the manufacturer side. With this information, a contractor with a meter on a pressure washer could show a customer the economy of the approach.