Pollution-Related Challenges: Sharing in Good Outcomes Requires Sharing in Responsibility

By Diane M. Calabrese / Published March 2014

Sharing does not always come easily to us humans. Yet we do share a planet and its life-supporting layers of air, soil, and water. As such, working out the details of how to be productively engaged without injuring the environment of our neighbors and ourselves is not a recent concern. For at least 5,000 years, a tug and pull over how water will be used—and kept clean—has gripped communities ranging from the ancient Mohenjo-Daro (Indus Valley) and Babylonian civilizations to the over-lapping cattlemen and farmers in the American West.

Today, air quality issues conspicuously link everyone on the planet. So, too, do concerns tied to arable soil, which are typically expressed more quietly. Rules and regulations have proliferated, at their most fundamental level as reminders for everyone to do the right thing. And that is to contain contaminants that could pollute air, soil, and water. Perhaps the biggest pollution-related challenge that industry members confront is keeping pace with the rules and regulations. Local, state, and federal entities all have a say. In that regard, expect the unexpected.

“A big concern that we’ve run into recently, in southern California, is the ‘smell police,’” says AC Lockyer, the owner of SoftWash Systems, headquartered in Winter Springs, FL. “Literally, people can complain about odors.” Indeed they can. Odor complaints receive formal attention well beyond one Air Quality Management District in the Golden State. Lockyer’s report prompted this writer to check her home base of Montgomery County, MD, where the Outdoor Air Quality Ordinance encompasses odors. Moreover, the county offers a specific complaint form, the Citizen’s Two-Party Odor Complaint Form, which is to be used for reporting offending odors to officials.

In the California instance, explains Lockyer, it means that solvents used for cleaning or chemicals used for pest control might require a variance. The process of securing the variance requires thorough documentation to demonstrate that the odor is innocuous. The proof is left to the contractor. So a distributor or manufacturer available to assist with documentation is important.

“I think education is the key to success for contractors,” says Lockyer. “Get educated on what the law says.” Moreover, be sure to consider the many layers of regulators and the variety in expectations. In the case of wastewater, which at this juncture still attracts much more oversight than odors, the variation by place is enormous.

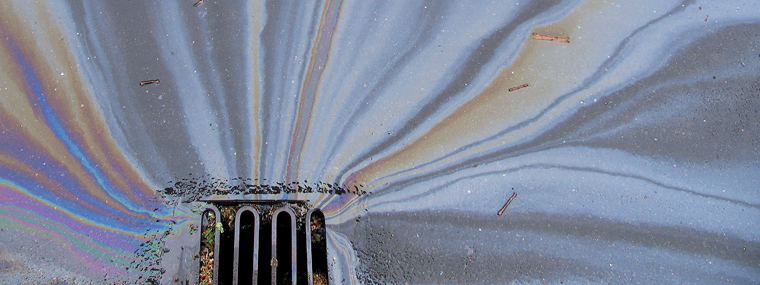

Ron W. Robarge, President and CEO of Pressure Power Systems/Vacu-Boom in Kernersville, NC, recommends to contractors that they always check with the local authority regarding the rules for using sewers and required treatment of wastewater. In some cases, wastewater that is pretreated might be eligible for disposal via a storm sewer.

Even in places where regulations regarding wastewater are a bit less restrictive than in California, contractors are moving forward on their own. “I feel changes coming,” says Kim Micha, CPA, Manager at High PSI Ltd. in Glendale Heights, IL. She explains that especially for wastewater collection there are more requests for equipment. Micha appreciates that contractors are taking the initiative, even in the absence of a specific rule. She believes it speaks well for the entire industry, an industry that is fundamentally concerned with the environment.

Pollution Control Experts

“Any reasonable person does not want to pollute the planet,” says Jerry McMillen, President of Sirocco Performance Vacuums in El Cajon, CA. But there will always be byproducts to human activity—whether it’s detailing or washing oil and grease off a fleet. “Contractors are really good people trying to do really good things in this industry,” says McMillen. They absolutely feel good about protecting the environment.

As the co-chair of the environmental committee for the UAMCC, McMillen has a special vantage. “I’ve been dealing with people on a national level, listening to what they are going through on a job site,” he explains. In wastewater control, one big issue is the “sporadic” nature of enforcement, says McMillen. Some contractors try to avoid projects that require collection systems, for example. But they then unwittingly step over a jurisdictional line and suddenly get cited for an infraction.

As the co-chair of the environmental committee for the UAMCC, McMillen has a special vantage. “I’ve been dealing with people on a national level, listening to what they are going through on a job site,” he explains. In wastewater control, one big issue is the “sporadic” nature of enforcement, says McMillen. Some contractors try to avoid projects that require collection systems, for example. But they then unwittingly step over a jurisdictional line and suddenly get cited for an infraction.

Conversely, individuals in enforcement may not have a thorough understanding of the industry. “We have this battle of interpretation,” says McMillen. Barricade, vacuum, sheet on sidewalk, etc.—which is best or the best combination? It depends.

“The bottom line is, what is the best available technology,” says McMillen. The technology that will control the wastewater in a way that brings the most sustainable outcome from the job site is the way to go.

In effect, says McMillen, the power washing industry should be renamed as the industry of pollution control experts. “People who understand the best available technology should be doing the education at the job site,” he explains. The education includes being able to respond in a cogent and persuasive way to all inquiries from regulators.

McMillen advocates for a focus on what can be done and how it can be done better and better with technological improvement. “Just saying, ‘You can’t do that,’ is a mistake,” he says. He envisions a day when all wastewater will be filtered to an acceptable level for the storm drain. It’s possible now, he explains, but still not cost effective.

Like Micha, McMillen sees contractors willingly adding the most up-to-date technologies for control of pollutants. “They are investing in the future of our sustainability,” he says. Yet, too often contractors who make such an investment lose out, says McMillen. “The contract cleaners’ biggest frustration is they invest in equipment and then don’t get the job,” he explains. “They lose out to someone who doesn’t have a reclaim system.”

Consistent enforcement of rules would level the playing field, says McMillen. Not infrequently, he has seen exemptions given for activities such as cleaning up after a street festival. “We’ve got to protect our environment,” says McMillen. But we must do it, he explains, in the context of understanding that there are going to be byproducts from economic activity. It is capitalism that makes pollution control possible.

A vigorous economy in a capitalistic economy rewards inventors, innovators, and all those who endeavor to get the job done in the most efficient and least intrusive way. A contractor who can use less water, generate less wastewater, and still produce an excellent outcome in the shortest possible time will boost his bottom line. Manufacturers and distributors who make such efficiency possible also benefit.

Truly Level Playing Field

A WaterSense at Work (page 146) entry at the Environmental Protection Agency website (www.epa.gov) puts it this way: “The most common method of compliance with the CWA [Clean Water Act] is to prevent wastewater discharges to waters of the United States.” It continues, reminding that if a discharge does not meet U.S. waters, there are no requirements.

Total containment of wastewater and then removal from a job site—if feasible—generally eliminates the need for a National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System [NPDES] permit. Otherwise an NPDES permit must be obtained by a power washer contractor for each discharge location. Even so, most NPDES permitted water still has to be treated and analyzed (contents verified) before being legally discharged.

Irrespective of which task a power washer tackles, there will be some environmental impact. There are engine emissions. There is the use of potable water—if not from an independent recycled supply—that reduces holdings of a community water supply.

In the day-to-day of business, contractors may simply remove dirt, mold, fungi, and bird droppings naturally occurring substances that would have entered the water supply or become airborne anyway. (Wind has whipped and water has carried for millennia.)

Sustained focus on industrial and cleaning processes means there is a big source of chemicals entering U.S. waters that has been largely ignored. It’s also growing. Late in 2013, an EPA study pointed to the need for attention to pharmaceuticals in water. Not only do prescription drugs make their way into water because some are thrown into toilet bowls and down drains, but they also enter the water via urine and feces. The more drugs taken, the more drugs move into the water supply. The EPA now has pharmaceutical compounds on its watch list, but they are not being restricted in the way that chemicals used as cleaning agents or solvents in industry are.

Sustained focus on industrial and cleaning processes means there is a big source of chemicals entering U.S. waters that has been largely ignored. It’s also growing. Late in 2013, an EPA study pointed to the need for attention to pharmaceuticals in water. Not only do prescription drugs make their way into water because some are thrown into toilet bowls and down drains, but they also enter the water via urine and feces. The more drugs taken, the more drugs move into the water supply. The EPA now has pharmaceutical compounds on its watch list, but they are not being restricted in the way that chemicals used as cleaning agents or solvents in industry are.

Just about anything humans imbibe or ingest ultimately reaches the water supply. For now, though, all the hormones (e.g., estrogen), pain medications, antibiotics, antidepressants, and so on, are not targeted by water treatment plants. Pharmaceuticals that are scooped with the sludge used as fertilizer further extend their range when sludge is applied to soil.

The EPA cites studies illustrating that pharmaceuticals generally show up in drinking water in amounts too low to harm. But studies of cumulative effects, as well as comprehensive and long-term studies, are needed. Existing studies do cause concern, such as those demonstrating estrogen and estrogen-like chemicals alter sex ratios in fish. Sharing in good outcomes—clean air, soil, and water—requires sharing in responsibility. Let us hope all soon will.